Christine Lagarde has urged countries to put a brake on austerity measures amid signs that the IMF is becoming increasingly concerned about the impact of government cutbacks on growth. Ms Lagarde, IMF managing director, cautioned against countries front-loading spending cuts and tax increases. “It’s sometimes better to have a bit more time,” she said at the annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank on Thursday.That’s from Thursday’s front page story on FT.com. To say it’s a big deal is possibly understating matters. Though, obviously, we had inklings that this sort of thing was to come as soon as the IMF released its latest World Economic Outlook this Tuesday, which highlighted the organisation’s disappointment with the fiscal multiplier effect being larger than previously anticipated.

The fund warned earlier this week that governments around the world had systematically underestimated the damage done to growth by austerity.

The fact of the matter is that the IMF has played bad cop to the global economy for generations now, enforcing austerity, conditionality and accountability wherever it goes. And, for the most part, it’s the emerging world that’s suffered most.

Recanting on some of these closely held beliefs, especially now that the bitter medicine is predominantly being applied to the developed world, is awkward to say the least. Some might even say it’s as close to an admission of past wrongs as you will ever get.

We ourselves shan’t rush to that conclusion because we don’t think it’s clear that the fiscal multiplier works the same way in every situation. The key point, we think, is that what we are discovering is that it’s variable. And that in some economic conditions it works much more effectively than we ever possibly hoped.

It’s no surprise that Paul Krugman, who warned about this being the case all along, is feeling a bit smuggish right about now (and rightly so).

As he wrote in his blog at the New York Times on Thursday, even the idea that fiscal consolidation is the result of low growth, not the other way round, doesn’t wash either:

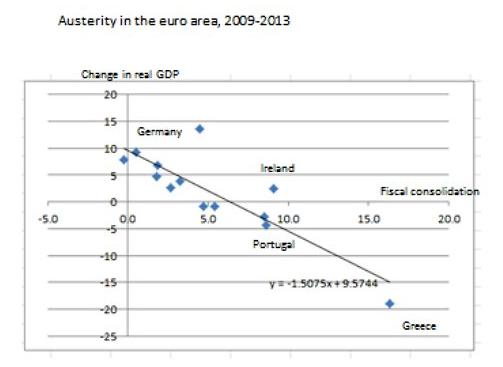

I and others have been arguing for a while that the experience of austerity in the eurozone clearly suggests pretty big Keynesian effects. Here, for example, is what a scatterplot of fiscal consolidation (from the IMF Fiscal Monitor) and growth (including an estimate for next year, from the World Economic Outlook) looks like:As Krugman notes, the key game changing finding from the IMF report is that activity over the past few years has disappointed more in economies which were implementing aggressive fiscal consolidation plans than those that weren’t. Which means the contractionary effects of fiscal consolidation are substantially bigger than policy makers were assuming.

But, you might object, maybe the causation runs the other way; maybe countries in trouble are forced into fiscal consolidation, so it’s not the austerity what did it. But the IMF has an answer to that: it looks at forecast errors versus austerity. Part of the reason for doing this is to figure out why things are going so much worse than expected; but there’s also the fact that the forecasts already included the known problems of the economies in question, so that you’re more or less getting an estimate of the impact of austerity over and above the known problems (and the initially assumed effect of austerity, which was supposed to be small).

The question is, what will the political elite do with this knowledge? Also, to what degree will the IMF have to stage a “we’re sorry” campaign?

Lastly, if we do all agree that more fiscal stimulus is needed, how do we ensure that stimulus is correctly distributed — and by that we mean to industries of tomorrow rather than to flailing industries of the past?

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2012/10/11/1205021/the-imf-game-changer/________________________________________

προκειμένου να εμπεδώσουμε καλύτερα το

greek fiscal multiplier: ΔΝΤ (2012) @ 1,5 vs. ΔΝΤ (old) 0,5

No comments:

Post a Comment